The 5 CEO Traits That Separate Wealth Creators from Value Destroyers

I’m sure you’re aware of the Buffett quote,

I try to invest in businesses that are so wonderful that an idiot can run them. Because sooner or later, one will.

The point of the quote, like so many of Warren’s quotes, is about finding exceptional businesses with large sustainable business moats.

The issue I have with the quote above is that an idiot in charge of such a wonderful business, can’t harm it. An idiot could really harm an exceptional business.

Microsoft is the most recent example that comes to mind.

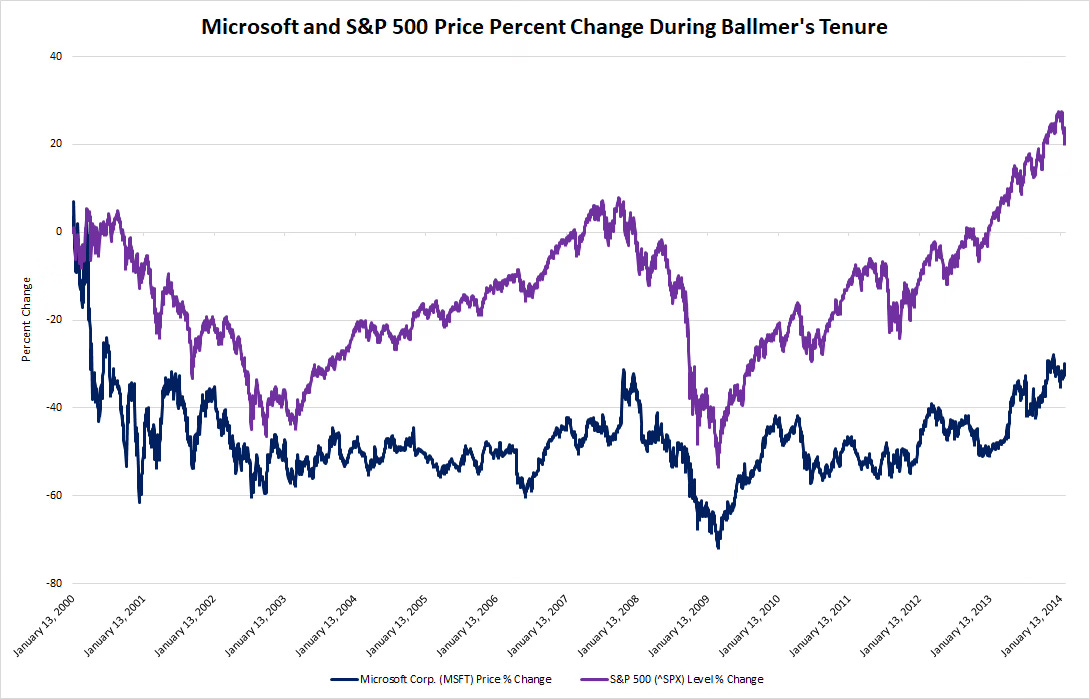

Steve Ballmer was named the CEO of Microsoft on January 13, 2000.

I wouldn’t call him an idiot, just a low-quality CEO.

It was the dominant technology company built on the rise of enterprise and personal computing. It built immense switching costs on top of its Windows Operating system and network effects with developers.

But Ballmer went defensive with Microsoft and missed the shift to mobile and smartphones.

There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. - Steve Ballmer

Once he realized their mistake Microsoft tried to get into the phone game instead of focusing on their strength, software. Ballmer and crew wasted billions on R&D and marketing to launch their own phone and operating system to near zero market share.

Then you have all his poor capital allocation decisions:

Buying aQuantive to compete with Google that lead to a $6.2 billion write down

Buying Skype for $8.5 billion and then letting the asset wither on the vine.

Buying Nokia for $7.2 billion as it was being disrupted by iPhones that lead to a $7.6 billion write down

Under Ballmer’s tenure, he was fired February 4, 2014, Microsoft returned -32.57% on a price basis while the S&P 500 returned 21% over that same time.

To be fair, Ballmer took over at the peak of tech bubble when Microsoft was very richly priced.

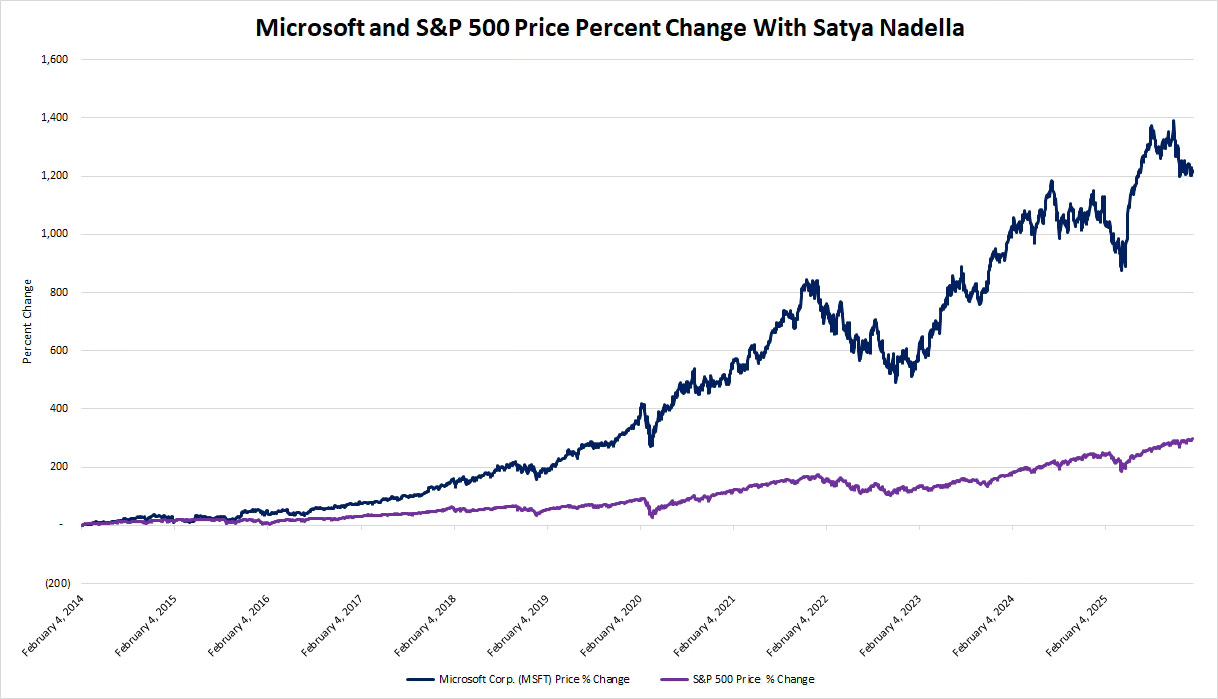

But what happens when we pair a wonderful business with a high-quality CEO?

Satya refocused Microsoft on what it does best, software. He rebuilt developer trust. And most importantly he invested heavily in where the market was heading, cloud computing.

The business model and competitive advantages matter, but the people running the company matter just as much.

These are the five traits that I think are important to look for when evaluating a CEO or founder. This is a qualitative assessment, not quantitative. It’s more art than science.

1. Visionary, Long-Term Orientation

We want CEOs who “have a visionary attitude towards the business’s opportunities” and can translate that vision into a concrete strategy for becoming a long-term winner. This isn’t about being a charismatic storyteller. It’s about investing based on what’s best for the customer and/or business over time. We want CEOs who act like long-term owners.

Example

Jeff Bezos at Amazon exemplified this trait.

His annual shareholder letters consistently reinforced a multi-decade time horizon, willingness to accept short-term losses for long-term customer value, and resistance to quarterly earnings pressure.

When Amazon invested heavily in AWS infrastructure despite years of losses, or built out logistics networks that wouldn’t pay off for a decade, Bezos was demonstrating owner-like thinking because he was and still is Amazon’s single largest individual shareholder.

Questions to ask

Does the CEO’s compensation structure reward long-term value creation (multi-year vesting, stock ownership) or short-term metrics (annual bonuses tied to quarterly earnings)?

In earnings calls, does management focus on quarterly guidance or on investments that won’t show returns for 3-5+ years?

Where to look

Review the last few years of shareholder letters and earnings call transcripts. Map out capital allocation decisions. Are they investing for the long-term and trying to build durable advantages or are they more focused on on the next quarter?

Check insider ownership and executive compensation disclosures in the Proxy Statement to see if incentives align with long-term ownership.

2. Independent Thinking and Contrarianism

High-quality CEOs and founders think independently and exhibit original ideas.

They tend to question the status quo and pursue new ideas and initiatives, where they can find new pockets of value rather than copying competitors.

CEOs obsessed with replicating competitors are on a fast track to mediocrity.

Example

Reed Hastings at Netflix demonstrated this repeatedly.

They started with DVD-by-mail when Blockbuster dominated the rental market. They then pivoted to streaming before anyone else and then invested billions in original content when the conventional wisdom was to license.

Each move looked contrarian and risky, but Hastings had conviction in where the market was going, not where it had been.

Questions to ask

Does management justify strategic choices by referencing what competitors are doing, or by explaining unique customer insights and market opportunities?

Has the company pioneered genuinely novel approaches in its industry, or is it a fast follower?

Where to look

Study the company’s strategic pivots and compare them to industry timelines. Were they leading or following? In earnings calls and investor presentations, count how often management mentions competitors versus customers and proprietary insights.

3. Deep Customer and Market Insight

High-quality CEOs and founders have strong market insight and deep convictions about the problem they are trying to solve for customers. Ideally this is rooted in personal experience of that problem. This grounds the business in solving real customer pain rather than chasing abstract TAM projections.

Example

Brian Chesky at Airbnb lived the problem he solved. He couldn’t afford rent in San Francisco and rented out air mattresses in his apartment. That personal experience gave him visceral understanding of both host and guest needs.

When Airbnb was struggling early on, Chesky personally visited hosts and stayed in listings to understand quality issues, demonstrating his customer obsession.

Questions to ask

Does the founder have firsthand experience with the customer problem, or did they identify an opportunity from market research?

Can the CEO articulate specific customer pain points with granular detail, or do they speak in generalities?

How often does the CEO reference direct customer interactions versus data dashboards?

Where to look: Research the founder’s origin story. What led them to start this company? In earnings calls and interviews, listen for specific customer anecdotes versus generic market analysis. Check if the CEO still engages directly with customers (customer calls, site visits, product usage).

4. Genuine Passion and Competitive Drive

High-quality CEOs and founders show genuine excitement for their products and love what they do. Their passion translates into a competitive drive to continuously improve their products or service. Their focus isn’t simply about building a big business —that’s a byproduct of being hyper-focused on providing the best product or service they can.

Example: Jensen Huang at NVIDIA has led the company for over 30 years with relentless competitive intensity. Even after NVIDIA became a leader in GPUs, Huang pushed into AI accelerators, autonomous vehicles, and data center computing. In interviews, he displays deep technical knowledge but also genuine excitement about parallel computing and AI.

Evaluation questions:

Does the CEO demonstrate deep technical or domain expertise, or do they rely heavily on prepared remarks?

Is there evidence of “enough is enough” thinking, or does the CEO constantly push for the next breakthrough?

How does the CEO react to setbacks?

Where to look: Watch long-form interviews and conference presentations where the CEO goes off-script. Read employee reviews on Glassdoor and Blind for cultural signals about leadership intensity and standards.

5. Owner-Like Discipline Over Empire Building

High-quality CEOs and founders have the patience and discipline to invest in organic growth and the willpower to resist “transformational”, and often value-destructive, acquisitions. This capital allocation discipline is essential. It protects returns on capital and focuses on compounding steadily rather than pursuing growth for growth’s sake.

Example: Mark Leonard at Constellation Software has built one of the best-performing stocks of the past two decades by acquiring hundreds of vertical market software companies, but he did so with a strict capital discipline.

Constellation walks away from deals that don’t meet strict return hurdles, maintains decentralized operations to avoid bloat, and refuses to overpay for growth. Leonard’s annual letters are a masterclass in disciplined capital allocation.

Evaluation questions:

What is the company’s track record on M&A? Disciplined and value-accretive, or serial disappointments?

Does management clearly articulate return hurdles and walk away from deals, or do they chase “strategic” acquisitions regardless of price?

How do they prioritize among growth investments, and what’s their willingness to return capital when opportunities are scarce?

Where to look: Build a spreadsheet of all significant acquisitions and capital allocation decisions over 5+ years, then evaluate returns. Read the capital allocation section of annual letters and proxy statements. Track return on invested capital (ROIC) trends and returns on incremental invested capital (ROIIC). Disciplined allocators maintain or expand ROIC even as they grow.

Why Great Businesses Need Great Leaders

Quality investing isn’t just about finding companies with enduring competitive advantages because in the wrong CEO’s hands, even a wonderful business can be destroyed.

We need to find wonderful businesses with exceptional management. Management that thinks and acts like long-term owners, even if they aren’t the largest individual shareholder. Management that brings independent vision with real market and customer insight. Management that understands where the industry is headed instead of copying peers. Management that possesses deep technical knowledge of their product and market, and is obsessed with solving customer problems.

These traits don’t guarantee success — a little luck is still needed — but their absence almost guarantees mediocrity. The durability of returns depends on leadership that can sustain excellence over decades, not just quarters.